One of the AL All-Star starting pitchers in 2024 employs a pitching arsenal unlike the rest of them.

Tanner Houck is a 28-year-old, 6’5 RHP from The University of Missouri. He was selected 24th overall in the 2017 MLB Draft by the Boston Red Sox. His inaugural season as a major leaguer in 2023 was pedestrian, posting a 5.01 ERA over about 100 innings. A paradigm shift began when the Red Sox hired Andrew Bailey as their pitching coach this past season. Bailey’s pitching philosophy has transformed the approach of his starters like Houck, steering away from the foundational pitch of most other successful pitchers: the 4-Seam Fastball.

Bailey, the 2009 AL Rookie of the Year and former bullpen teammate with current Red Sox GM Craig Breslow, implemented his strategy immediately. And, through the first 35 games of the season, the starting rotation had produced the lowest ERA (2.10) since the 1981 Dodgers (2.06) in that number of games. To that point, just 32% of their pitches had been fastballs, far below league average of 47%.

The proportion of fastballs seen in the MLB has been steadily dropping since 2008 (57%), with the expansion of secondary pitches, but the Red Sox have fully leaned into the trend.

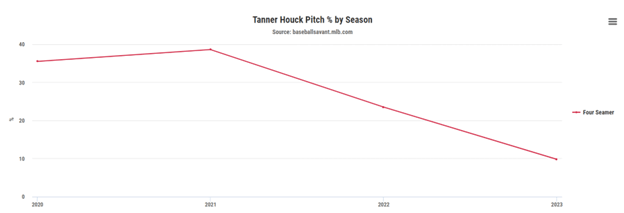

Going into the 2024 season, Bailey reshaped Houck’s repertoire by eliminating his ineffective 4-Seam Fastball. In 2023, that fastball had a .432 wOBA against (more than 100 points above league average) with a .333 BA against and a meager 15% whiff rate. He went from using the pitch 10% of the time in 2023 to 0% in 2024.

Houck % of 4-S Fastballs by year (per baseballsavant)

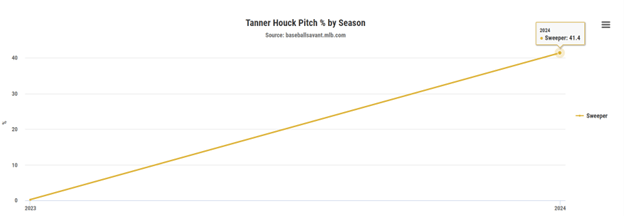

Andrew Bailey thought: Instead of clinging to the fastball solely out of convention, he’d rather Houck re-tool his arsenal around his only plus pitch in 2023, his slider (+8 Run Value in 2023). In fact, he more than doubled the average horizontal break on his slider in 2024 (from 8 inches to 17 inches), making it more of a sweeper than a slider.

In April, Bailey said, “The history of baseball suggest that fastballs have more damage attached to them… so looking at our fastball rates from last year, there’s some low-hanging fruit there and leveraging our weapons that generate weak contact…”

Houck % of Sweeper by year

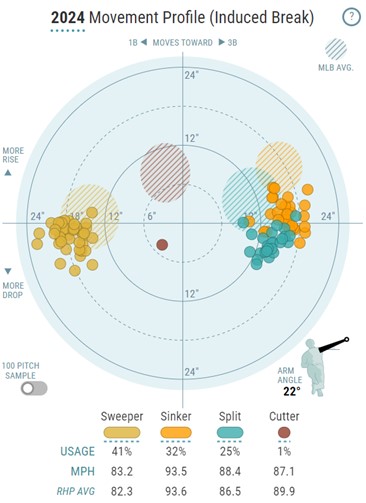

He established Houck as what’s termed an “East-West” pitcher, relying on pitches that move left and right rather than up and down.

Houck Movement Plot

In the movement plot above, his sweeper gets 2.4 more inches of break more than the average, and his splitter gets about 2.9 inches more tail above average. Throwing the sweeper 41% of the time makes Houck unique, with a definite performance boost.

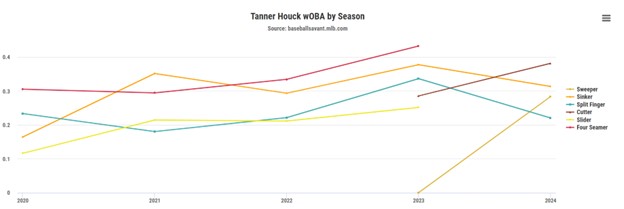

In the plot above, his sweeper in 2024 boasts a wOBA of .283 with a .230 BA against, about 10% better than the league average, driving his All-Star season. The splitter makes for an effective secondary pitch with a .234 wOBA while his sinker is weaker.

The sweeper is also his only real swing-and-miss inducing pitch, with a proficient 29% K rate and a 30% whiff rate. The sinker yields a less inspiring 16% K rate and 14% whiff rate. Meanwhile, this sinker also gets hit hard (95+ exit velocity) at a discouraging 48% rate.

This begs the question, should Houck remove ALL fastballs entirely, if the sinker (2-seam fastball) is his weakest pitch? I would say no, because breaking pitches don’t become effective in isolation. You can’t solely judge a pitch type based on its individual performance, without taking the other types into context. Part of the sweeper’s potency surely is attributable to the existence of his sinker, albeit a mediocre one. You need the zippy, arm-side moving sinker to set up the loopy, glove-side moving sweeper. It’s analogous to boxing, in which the jab is used to set up the knockout punch. A challenge in pitching analytics is discerning whether the effectiveness of a particular pitch type is intrinsic, or in its relation to others.

I think that Houck’s regression over the second half of the 2024 season indicates that he’s still gauging how to distribute his pitches among the sweeper, sinker, and splitter. In the first half of the season, he earned his all-star status with a meager 5% walk rate which was near the top of the league. This also resulted in a 18% K minus BB rate, showcasing elite ability to mitigate free passes while inducing swing-and-miss. However, in the second half of the season, the walk rate ballooned a little bit to 9% and produced a weaker 8% K minus BB rate. His control of the strike zone waned, and he was punching out much less hitters. His FIP almost doubled from 2.60 to 4.36.

While I think a small portion of the regression is due to fatigue, as he superseded previous high in innings pitched by +68%, there’s evidence that suggests that there’s more strategic experimentation to be done next year.

For example, let’s take a look at how the performance of his trademark sweeper tracked over the later months:

April: Usage%: 42%, SLG allowed: .219

July: Usage%: 45%, SLG allowed: .394

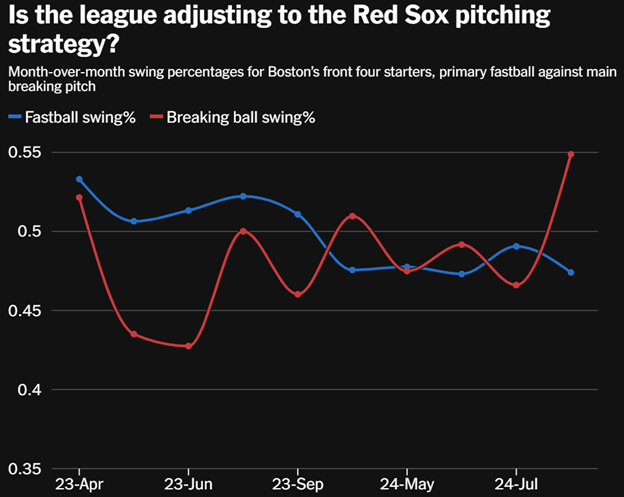

The Red Sox as a whole received a counterpunch from hitters late in the season. After the All-Star break, they had the 29th ranked starter ERA with an MLB-worst 2.2 HR/9, and a .489 SLG on breaking balls.

This regression indicates that major league hitters began to acclimate to Houck’s unique movement profile.

From NYTimes, Per the Athletic, baseballsavant

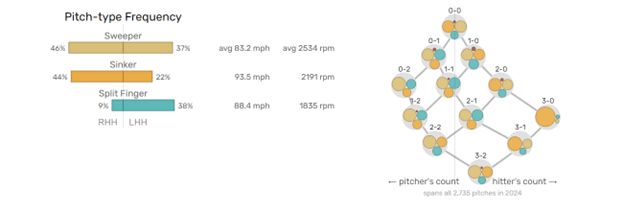

Reference the following visual from baseballsavant to contextualize Houck’s pitch selection based on the count:

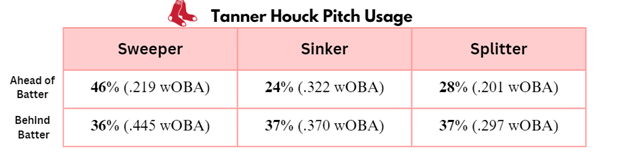

Examining the flow of pitch distribution through different counts, it’s clear that Houck leans heavily on his reliable sweeper when ahead of the batter (0-1, 0-2, 1-2). In each of these counts, the sweeper accounts for the most usage out of all his pitch types. However, that trend is almost inverted in hitter-friendly counts. Houck resorts to his sinker most heavily in 2-0, 3-0, and 3-1 counts, while the sweeper takes a back seat. This tendency indicates that Houck’s sinker ball usage, although lower than the sweeper, is particularly concentrated in these counts. I think that this distribution of pitch types among pitch counts contributed to his regression and predictability after the All-Star break.

The first aspect of this chart that jumps out is the decrease in Sweeper usage as you shift the count leverage from Houck to the batter. This also accompanies a dramatic drop in effectiveness, from a .219 wOBA allowed to a .445 wOBA (MLB avg ~.315). We can see the evident lift in sinker usage in hitters’ counts with a sub-par .370 wOBA.

Ultimately, I think that this breakdown demonstrates Houck’s lessened confidence in his breaking ball moving into hitters’ counts. He lost control of it late in the season and it got hit around during these situations, which caused him to default to the more straightforward sinker. I think that he could benefit from mixing in the “jab” aka sinker a bit more earlier in counts, so he’s not using it as much of a ‘get back into the count’ pitch. This could also help his wicked sweeper sustain its deceptive nature late into seasons.

Although I do think Andrew Bailey’s overall philosophy has proven to be legitimate for Houck, now a counterpunch to the counterpunch must take place.

A data point like this are what drives Bailey’s philosophy:

2023 Batting against Fastballs and Sliders:

Fastball: .269/.354/.447

Slider: .220/275/379

Clearly, it was entirely logical for Bailey to capitalize on the discrepancy in the numbers above, especially given Houck’s unique ability to spin a sweeper across the plate. However, it again needs to be established that much of the time, the breaking ball is threatening because of its supplementary role to the fastball. It’s logical that Houck should continue emphasizing his best pitch, but also continue to break his own tendencies in the future.

Subverting hitters’ expectations while playing to your strengths as a pitcher is the name of the game. Even without a deadly fastball, Tanner Houck can continue to be an All-Star caliber player by spinning his breaking balls and mixing in his “jab”.

Leave a comment